Animating GridViewItems with Windows.UI.Composition (aka the Visual Layer)

If you’ve ever used the beta version of myTube! (and you should), you’re probably familiar with the effect I wanted to create:

I absolutely love this effect, and when I accidentally open the non-beta version of myTube, where it’s not yet implemented, I miss it, often to the point of closing the app and opening the beta. It really makes for a great experience, so I wanted to create something like it myself. Here’s the result of what we’ll build in this post:

XAML

Let’s start with the XAML we’ll use to define the GridView:

<GridView SelectionMode="None" IsItemClickEnabled="True" HorizontalAlignment="Center" VerticalAlignment="Center" Padding="16">

<GridView.ItemContainerStyle>

<Style TargetType="GridViewItem">

<Setter Property="Margin" Value="6" />

</Style>

</GridView.ItemContainerStyle>

<GridView.Items>

<SolidColorBrush Color="LightSkyBlue" />

<SolidColorBrush Color="LightGreen" />

<SolidColorBrush Color="LightSalmon" />

</GridView.Items>

<GridView.ItemTemplate>

<DataTemplate>

<Grid Loaded="Item_Loaded">

<Rectangle Fill="{Binding}" Height="100" Width="100" />

</Grid>

</DataTemplate>

</GridView.ItemTemplate>

</GridView>This creates a GridView with three rectangles in the colors defined in GridView.Items and enough spacing between them to fit

the scaled-up rectangle and its shadow. Notice the

Item_Loaded event handler in the ItemTemplate,

that’s where we’ll set up our animations.

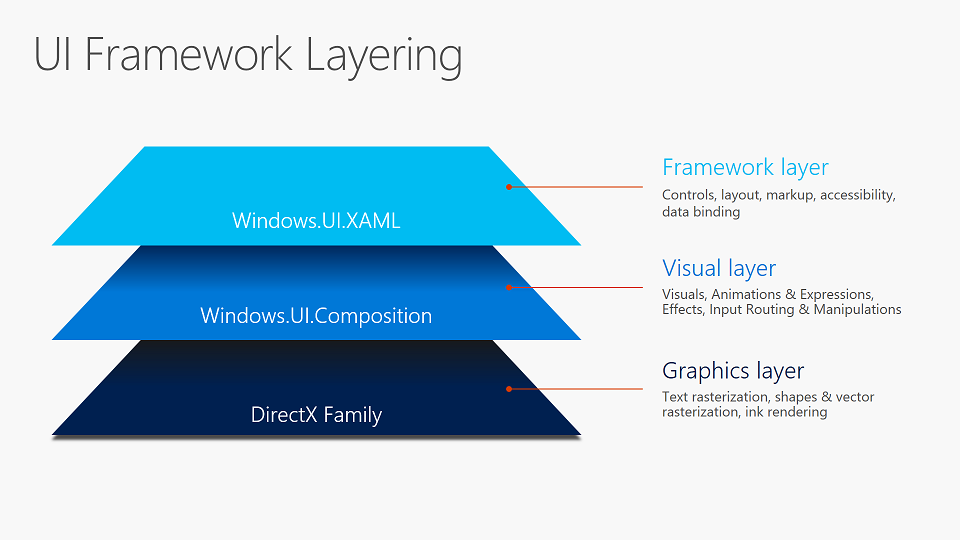

The Visual Layer

Before we go on and animate the GridViewItems, its worth to take a look at the technology we’re going to use. The Visual layer is the part of the Windows UI stack that supports the XAML Framework. This means that every XAML element has a representation in the Visual layer, but also that you could draw your entire application using the Composition API (the API surface of the Visual layer) without ever touching any XAML. Or build an alternative UI framework, if that’s your type of thing. The Visual layer also provides a way to do animations, lighting and shadows, and numerous effects.

Of course, there’s a way to get the Visual of any XAML element, which

can then be used with all the magic of the Composition API. This is done

using the ElementCompositionPreview.GetElementVisual()

method, which returns the backing Visual for any XAML element. Besides

the generic Visual type (which

GetElementVisual() returns) there are two deriving classes: a ContainerVisual, which is a Visual that has the ability

to create children; and a SpriteVisual, which can be

associated with a brush, so that it can render images, solid colors,

effects etc. The latter two are more useful when creating Visuals using

Composition, rather than manipulating XAML generated Visuals.

The last important part of the Composition API that I want to mention

here is the Compositor, which is the class that brings all

Composition elements together. It is used to create visuals and

animations (as well as lights, brushes, easing functions and other

related things), and it makes sure that changes to visuals are actually

applied and shown on the screen.

Scaling our rectangle

We start by having the Item_Loaded event handler call a

method to set up our animation, which takes a UIElement to animate. The

sender of the event (the Grid in the

ItemTemplate) is passed into that method:

private void Item_Loaded(object sender, RoutedEventArgs e)

{

var root = (UIElement)sender;

InitializeAnimation(root);

}

private void InitializeAnimation(UIElement root)

{

// Here comes the interesting stuff

}Inside InitializeAnimation() we first have to get the

Visual that backs the XAML element we got as the root

argument. For this we use the ElementCompositionPreview

class I already mentioned. We also get the compositor from the visual we received:

var rootVisual = ElementCompositionPreview.GetElementVisual(root);

var compositor = rootVisual.Compositor;Then we use the compositor to create a new

Vector3KeyFrameAnimation. Let’s decompose that word to

understand what we’re doing. First of all, it’s an Animation,

specifically a KeyFrameAnimation, which means that we can give it some

information about what we want the values to be at some points in time

and it will figure out the full animation from that. It animates a

System.Numerics.Vector3, also known as a 3-dimensional

vector. For those not familiar with linear algebra, it simply represents

a point in three-dimensional space, with an X, Y and Z coördinate. We

need a Vector3 in this case because we want to animate the

Scale property of our visual, which is a Vector3 for

scaling a visual in three dimensions, where the coördinates are not a

point in space, but the scale multiplier in that direction.

(I’m not sure what it means to scale an element in three dimensions

in this case, especially because the Size property of a

visual is a two-dimensional vector with just width and height. Please

let me know if this makes sense.)

var pointerEnteredAnimation = compositor.CreateVector3KeyFrameAnimation();

pointerEnteredAnimation.InsertKeyFrame(1.0f, new Vector3(1.1f));When the pointer enters the element, we want to scale it up by 10%,

so we add a keyframe at the end of the animation with a value of a

Vector3 with three times 1.1, to scale 1.1 times as big in all

directions. The first float is a normalizedProgressKey, so

0.0 is always the start of the animation and 1.0 the end, independent of

the duration. If there’s no start value defined (i.e. at key 0.0), the

current value of the animated property is used.

Similar to the pointerEnteredAnimation, we can define an animation for when the pointer exits the element, animating the scale back to 1.0:

var pointerExitedAnimation = compositor.CreateVector3KeyFrameAnimation();

pointerExitedAnimation.InsertKeyFrame(1.0f, new Vector3(1.0f));Now the only thing left to do is starting the animation when the pointer enters or exits or element:

root.PointerEntered += (sender, args) => rootVisual.StartAnimation("Scale", pointerEnteredAnimation);

root.PointerExited += (sender, args) => rootVisual.StartAnimation("Scale", pointerExitedAnimation);A Visual has a method to start an animation on one of its properties. The first argument is the name of the property you want to animate (yes, as a string, wait until we get to expressions), the second is the animation.

And that’s the result:

The animation works. But there are some problems design-wise: the animation plays oriented from the upper left corner, so the rectangle seems to expand on the right and bottom side, not from the center; and the hover border of the GridViewItem is shown inside the rectangle.

Some small improvements

First, we’ll make the animation play from the center. The Visual

class has a property CenterPoint, which defines the point

from which the visual is scaled and around which it is rotated. I’ve

found that the best place to set the CenterPoint is in the

PointerEntered event handler, right before starting the animation:

root.PointerEntered += (sender, args) =>

{

rootVisual.CenterPoint = new Vector3(rootVisual.Size / 2, 0);

rootVisual.StartAnimation("Scale", pointerEnteredAnimation);

};Here we set the CenterPoint (a Vector3 again, so you can also set the

depth of the center) to the center of the visual by using the

(Vector2 XY, float Z)-constructor. This will make sure all

animations look centered when the pointer enters the item. Setting it

again in PointerExited is not necessary unless you’re planning to change

the size (not to be confused with scale) of the element while the

pointer is on it. If you’re not changing the size of the element at all,

it might seem more logical to set the CenterPoint when also creating the

animations etc., but I’ve found during my experiments that that will

result in CenterPoint <0,0,0> because the returned Size is

<0,0>. I’m not sure why that happens, so again, please let me know

if it makes sense.

Next, I decided to entirely remove the hover and reveal borders of

the GridViewItem. They’re no longer useful because we already have a

differentiated hover state and they only add useless clutter. Removing

the borders involves retemplating the GridViewItem, and since the

template for a GridViewItem is rather large, I won’t paste it here, but

it can be found in this

Gist. In case you want to do it yourself: instead of the default

GridViewItem style, I based it on the GridViewItemExpanded

style, which you can find in generic.xaml, which already

removes the Reveal effects. In the template, I simply removed the

BorderRectangle and all references to it. Then that does

the job:

<GridView.ItemContainerStyle>

<Style TargetType="GridViewItem" BasedOn="{StaticResource BorderlessGridViewItem}">

<Setter Property="Margin" Value="6" />

</Style>

</GridView.ItemContainerStyle>

Adding a shadow

To really give a sense of depth when scaling up the rectangle, I wanted to add a shadow. To create a shadow you need a XAML element of the same size as and behind the element that casts the shadow. Then using the Composition API you can create a SpriteVisual, to which you add the shadow. Finally the shadow visual is added to the XAML element.

So first we need a container (e.g. a Canvas) for the shadow behind our rectangle:

<Grid Loaded="Item_Loaded">

<Canvas x:Name="ShadowContainer" />

<Rectangle Fill="{Binding}" Height="100" Width="100" />

</Grid>To create the shadow in InitializeAnimation(), we also

need to know where to put our shadow, so now the method takes a second argument:

private void InitializeAnimation(UIElement root, UIElement shadowHost)

{

...

}

private void Item_Loaded(object sender, RoutedEventArgs e)

{

var root = (UIElement)sender;

InitializeAnimation(root, FindVisualChild<Canvas>(root));

}The FindVisualChild method returns the first child of a type and is adapted from here. You can also find it in this Gist.

Now back to InitializeAnimation. First, we get the

visual for our Canvas (shadowHost, from now on), we’ll need that later.

Then we create a new DropShadow, set its color, create a new

SpriteVisual to hold the shadow, add the shadow to that visual, then add

that visual to the shadowHost.

var shadowHostVisual = ElementCompositionPreview.GetElementVisual(shadowHost);

// Create shadow and add it to the Visual Tree

var shadow = compositor.CreateDropShadow();

shadow.Color = Color.FromArgb(255, 75, 75, 80);

var shadowVisual = compositor.CreateSpriteVisual();

shadowVisual.Shadow = shadow;

ElementCompositionPreview.SetElementChildVisual(shadowHost, shadowVisual);We also need the following snippet to resize the shadow as the shadowHost changes size. I’ll explain how it works later when we write our own ExpressionAnimation.

var bindSizeAnimation = compositor.CreateExpressionAnimation("hostVisual.Size");

bindSizeAnimation.SetReferenceParameter("hostVisual", shadowHostVisual);

shadowVisual.StartAnimation("Size", bindSizeAnimation);With this code we have added shadows to our rectangles:

The next step is, of course, to animate the shadow, so that it

doesn’t show when the Scale of the rectangle is 1.0, and it shows

increasingly when the rectangle is scaled up. To achieve this we can

animate the BlurRadius property of the shadow. And to do

this we’ll have to use an ExpressionAnimation, so let’s take a look at

how those work.

Expression animations

The way I think about an expression animation is like a binding,

possibly with a converter. Let’s take a look at the resizing snippet to

see what I mean. The result of that animation (read binding) is that the

shadowVisual always has the same size as the shadowHostVisual. An

ExpressionAnimation is created with the expression

"hostVisual.Size" (I promised you, more strings) and in the

next line "hostVisual" is defined to be a

reference to the shadowHostVisual. The resulting animation

always returns the value of shadowHostVisual.Size. To bind

that value to the size of the shadowVisual, the animation is started on

the Size property.

Binding the size is a fairly simple application of the Expression language, which allows you to do much more powerful things by using the available keywords and functions. You can also set various numerical values as parameters, not just references to visuals, so that you can build generic expressions.

It’s also worth noting that an expression animation has no finite

duration, so it doesn’t end by itself. For an animation that’s unusual,

but it makes sense if you’re thinking about it as a binding. Of course,

you also have to make sure that the resulting type of the expression is

the same as the type of the property you want to animate. So for

animating a Size property, the expression has to result in a Vector2 etc.

Now we want to bind BlurRadius of a shadow to the Scale of a

rectangle. So the input of our expression will be a reference to

rootVisual (which we animated to scale) of which we read

the Scale property with type Vector3 and the output will be

the BlurRadius of the shadow, which is a Float. Since we do

uniform scaling on our rectangle (the width and height are scaled by the

same number) we can simply read the X, Y or Z of the Scale property to

get our scaling factor as a float. If we call reference to rootVisual

source, our expression would then look like

"source.Scale.X".

We don’t want the shadow to be visible when the rectangle is not

scaled up, so when the scaling factor is 1.0, we want the resulting

BlurRadius to be 0. We can do that by changing the expression to

"source.Scale.X - 1". This will make sure that the

BlurRadius is 0 when the scaling factor is 1, but when we scale up the

rectangle to 1.1 the BlurRadius will be 0.1 pixels, which is practically

invisible. So we also have multiply this number with some constant to

get to a more visible shadow. I chose 100 to get a BlurRadius of 10px

when the rectangle is scaled up, but if you want more or less shadow

this is the number to tweak. Our final expression is

"100 * (source.Scale.X - 1)".

Now we only have to create an animation from our expression, set a reference to the rootVisual and animate the shadow:

var shadowAnimation = compositor.CreateExpressionAnimation("100 * (source.Scale.X - 1)");

shadowAnimation.SetReferenceParameter("source", rootVisual);

shadow.StartAnimation("BlurRadius", shadowAnimation);And that’s what it looks like:

Closing remarks

The complete source for the final version is available in this Gist.

If you don’t want to scale uniformly, you might want to change the

shadow expression to be based on both the X and Y component. Something like

"100 * ((Sqrt(Square(source.Scale.X) + Square(source.Scale.Y)) / Sqrt(2)) - 1)"

could do the trick. If you don’t like the idea of writing that in a

string, you can use the ExpressionBuilder

project. It’s not on NuGet, so you’ll have to copy over the source.

The choice is yours.

If you were planning to use this in combination with a SwipeControl, I’m sad to say that I couldn’t get it working. The SwipeControl somehow prevents its content from scaling out of its own size so the edges will be cropped. My solution is to instead use the deprecated SlidableListItem from the Windows Community Toolkit and it works wonderfully:

Finally, Composition is not an easy topic and good resources are rather scarce, so I recommend experimenting a lot to get a grasp on how it works. Here are some resources that might help you:

- Documentation: conceptual and API reference. Of the conceptual docs Using XAML is probably the least confusing article. I think most of the documentation is only useful if you already know a bit about Composition.

- I recommend letting the WindowsUIDevLabs Sample Gallery wait until you have a good grasp of what’s going on, but the Reference Demos might be helpful.

- Mike Taulty’s blog posts on experiments he did are really helpful.

- More resources are listed here. I’ve not looked at all of them, but some might be useful to you.