A Meta Perspective on a Refined Model of Ill-definedness

Last week my co-author Vadim Zaytsev presented our paper A Refined Model of Ill-definedness in Project-Based Learning at the Educators Symposium of MODELS 2022. Go read that paper first, or this won’t make much sense. In this post I try to answer a question we got afterwards.

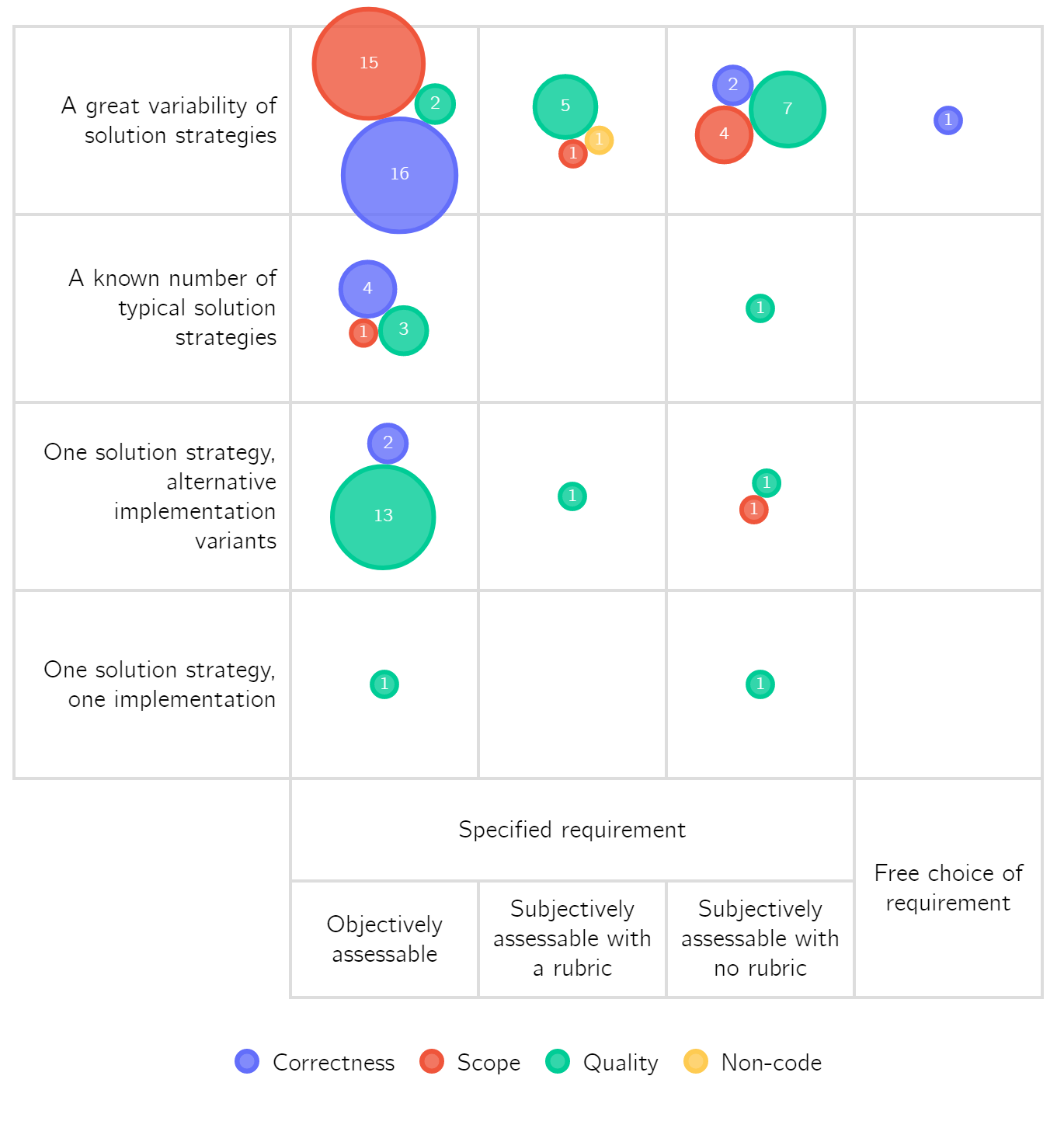

If you need some convincing to read the paper, or just want a short summary: the goal of the paper is to shed some light on what it means for an educational task to be ill-defined. For an ill-defined task there are many possible solutions; experts can disagree on which solution is better and there is no formal theory to determine or test outcomes; reaching the goal requires the design of new artefacts or analysis of new information; and the problem can not be subdivided into independent subproblems. We recognize that there is a spectrum of ill-definedness and extend an existing two-dimensional (verifiability and solution space) classification. We then consider the assessment criteria for two programming projects at the University of Twente and place them in the classification. See the image below for an example.

After the presentation, Peter Clarke asked an excellent question about bootstrapping this model: can the model be applied to itself? Let’s try and see if it works.

What does the model assess?

The model assesses the ill-definedness of an educational problem through its assessment criteria. So, just like a student’s submission for a project is graded on how good it is according to certain criteria, we “grade” the project on how ill-defined it is according to certain criteria. To apply the model to itself, we only need to let go of one assumption, namely that a higher grade is better: we only make a call on how ill-defined a project is, regardless of whether an ill-defined project is good or bad. Now, the assessment of ill-definedness is just like the assessment of quality and we can use the model to determine how ill-defined our assessment of ill-definedness is.

To do so, we need to know the criteria on which we assess the ill-definedness of a project. In the model, both the original and our refined version, there are two criteria:

- The project has a large solution space.

- A solution is difficult to verify or assess.

If these are fulfilled, a problem is ill-defined. (Just like a solution or artefact is good, if it meets the assessment criteria.)

How do these criteria fit in the model?

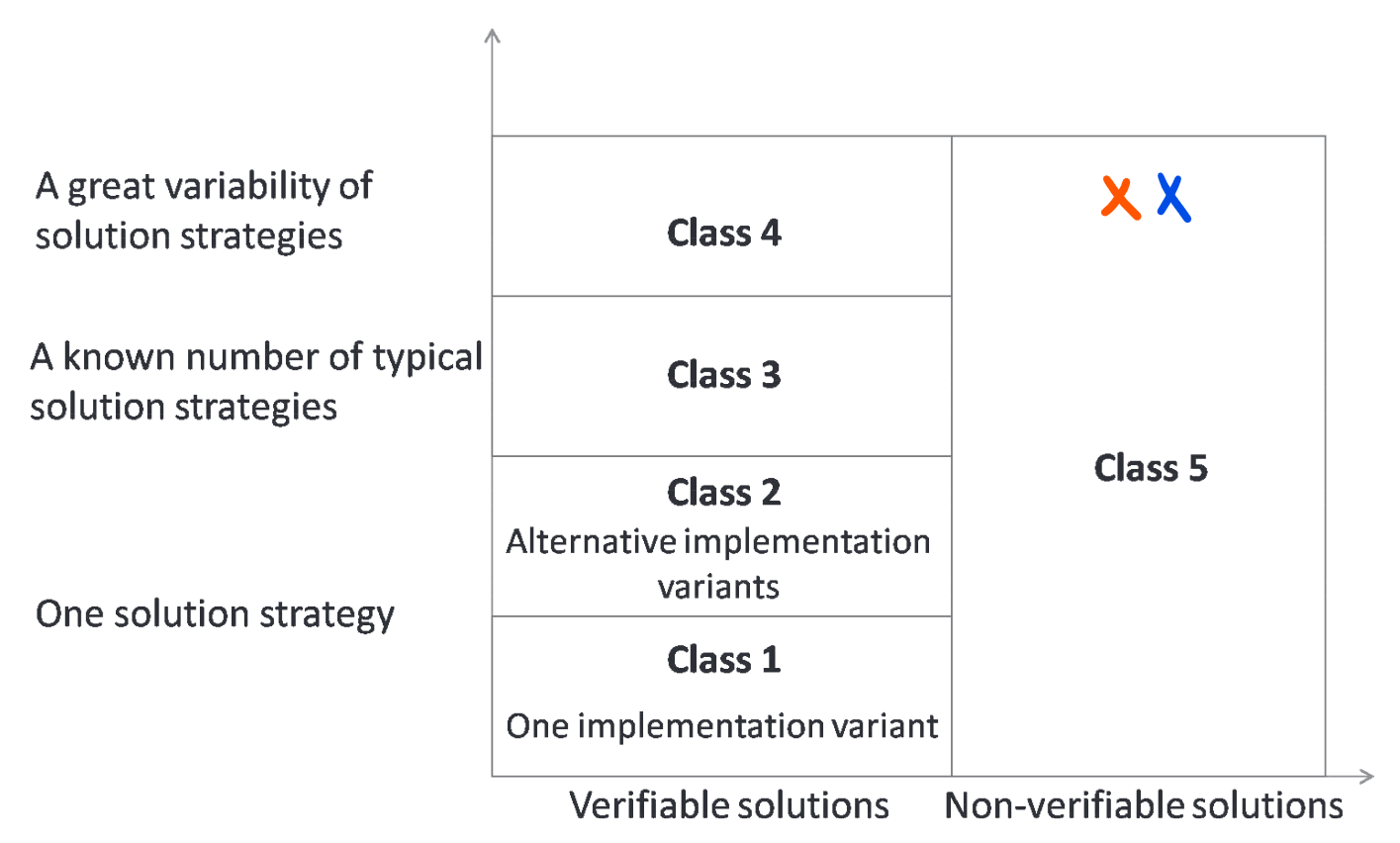

These criteria correspond the two axes used in the original model by Le et al. (2013). If we place the criteria in the original model, both end up in class 5. Both criteria are clearly at the top of the classification: there are many ways in which a project can have a large solution space and solutions that are difficult to assess. Whether the solution space has “great variability of strategies” is not clearly verifiable, and neither is the line between verifiable and non-verifiable clear-cut. This means that both criteria are non-verifiable.

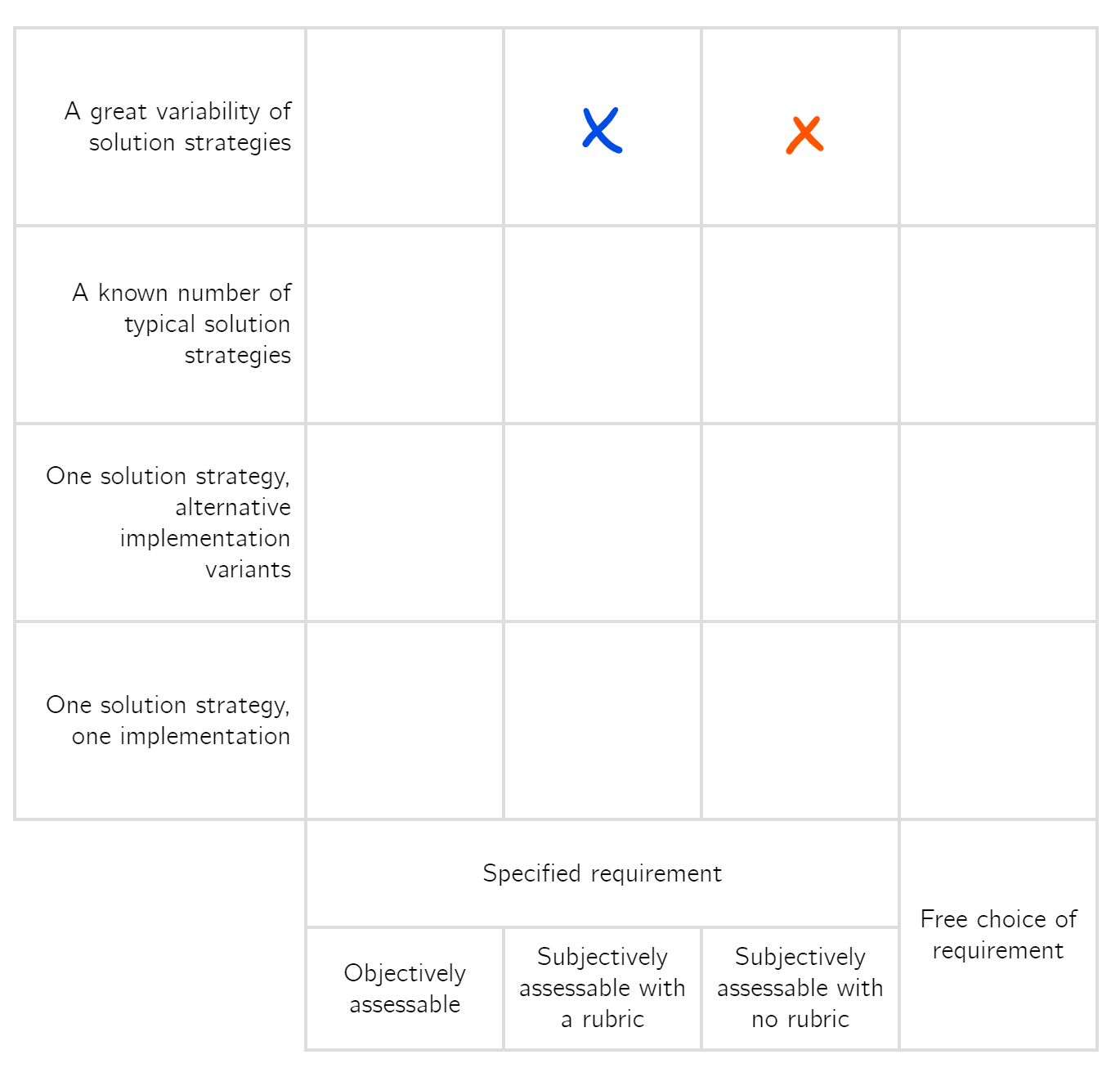

We can also place the same criteria (as used in the original model) in our refined model. Both criteria are placed in the top row, just like in the original model. The criterion on large solution space is in the subjectively assessable with a rubric column: the model provides a rubric that describes four levels of a large solution space. The “difficult-to-assess” criterion is in the subjectively assessable with no rubric column: we have to pick between verifiable and non-verifiable in the original model, which is a (partly) subjective choice. Some may find a certain criterion easy to verify, while others would say it is not verifiable.

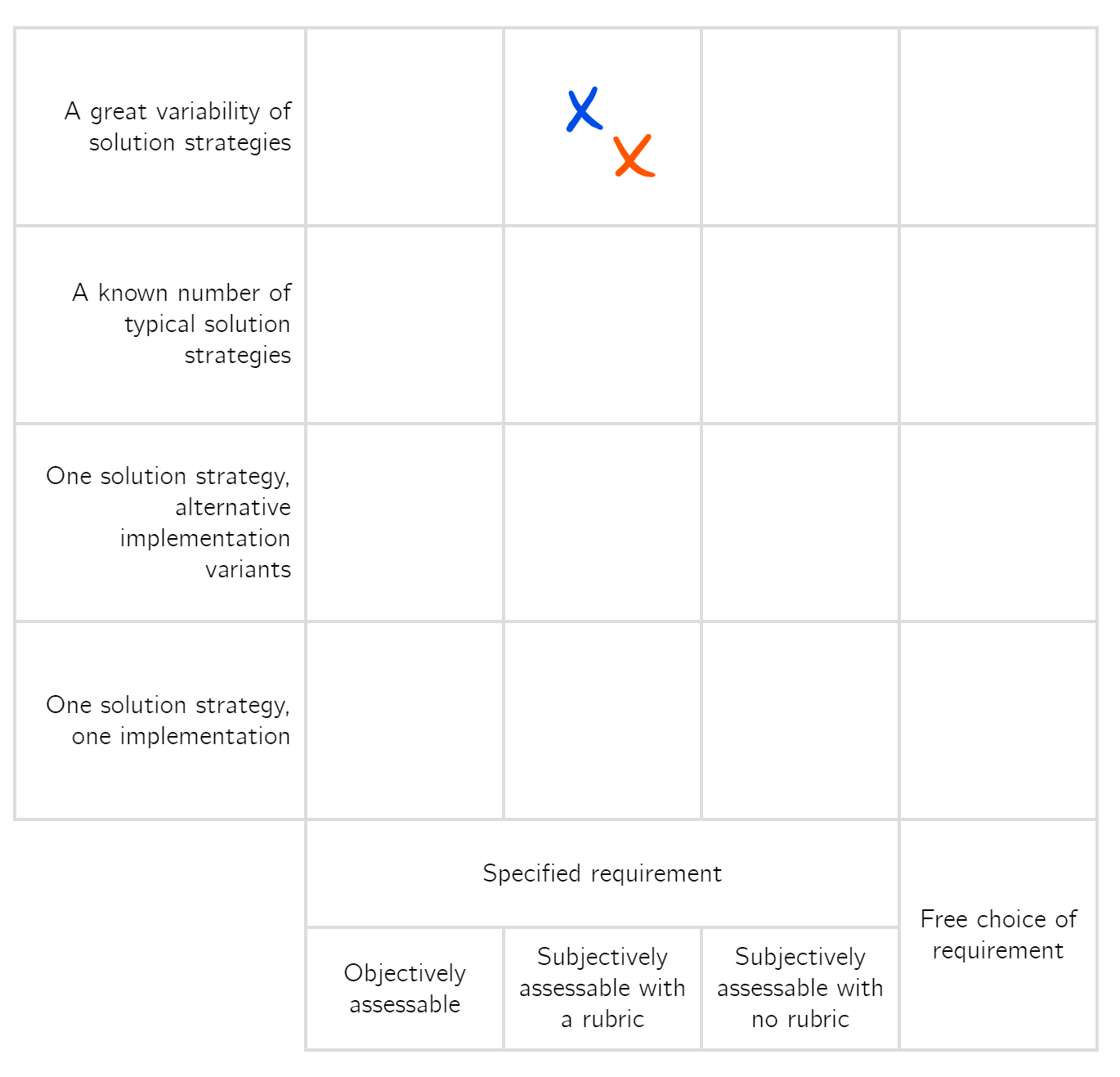

Then we can, of course, also place the criteria as used in the refined model in our refined model. Now the “difficult-to-assess” criterion has shifted one column to the left: instead of a subjective verifiable or non-verifiable question, our refined model provides a rubric to determine how difficult assessment for the criterion is. The rubric is part of a peer-reviewed publication, so we can even say that it is (at least somewhat) agreed upon.

What does this tell us about the model?

The shift to the left shows that our model makes it easier to assess how difficult it is to assess a solution. This means that we have made the question of ill-definedness less ill-defined. I will leave it as an exercise to the reader to determine if this is a proof that our model works, merely a proof of internal consistency, or just a circular argument.

Even better than making ill-definedness less ill-defined, I believe that, according to our model, our model is the optimal solution. Trying to make a more objective description for both criteria does not make the model more useful as a tool, so we can’t move the criteria further left. There also is no way to reduce the number of strategies to create an ill-defined problem in the real world, so we can’t move the criteria down in the model. That proves that our model is the best possible model.

Until someone decides to add another column, of course.

If you got the impression that I’m making fun of the question, you are only half right. I do find bootstrapping funny in general. Still, it is an important concept and certainly worth applying if you can. If it turned out that our refined model made the question of ill-definedness more ill-defined (according to our model), that would be a good reason to reconsider if we were really doing anything useful.